WINTER SIDEWALKS

There’s an extra challenge for pedestrians living in cities with winter weather that lasts for months of below-zero temperatures and snow. While municipalities can’t prevent cold weather, their policies and actions on clearing sidewalks have a significant impact on our ability to walk safely in the winter. Regina, Saskatchewan where Project Pedestrian originates, finally passed a bylaw in 2021 after years of awareness-raising, which requires residents to keep the sidewalks “free of snow and ice”. While some residents and businesses ignore the bylaw and some residents are physically unable to clear the snow and can’t afford to pay others to do it, sidewalks in Regina have improved since the bylaw was passed. However, it’s the rare block where every property has made their stretch of sidewalk passable, and people who use canes, walkers, strollers, or wheelchairs are not able to navigate most of the city’s streets from November through March. It’s hard to understand why the City and many of its residents think this is an acceptable situation and that fixing it is impossible.

Many cities take on the responsibility to clear the sidewalks just as they do the roads. Toronto requires residents to clear the sidewalks in front of their properties, but when more than 2cm of snow has fallen, the City takes over. Montreal, which can get a lot of snow, commits significant resources into clearing snow from sidewalks and roads. Some cities heat their sidewalks so snow and ice can’t accumulate. Swedish cities adjusted their snow clearing policies to prioritize pedestrians after looking at things through the lens of equality, as the video below explains.

If heated sidewalks aren’t available and your city doesn’t clear the sidewalks, you need to make sure your footwear has the best possible grips for ice and snow; this study by the KITE Research Institute led to the purchase of the best gripping snow boots I’ve ever had, though the long strides of summer and autumn still have to be replaced by penguin-like scuttling across the most treacherous stretches. Fingers crossed I make it through the winter without a slip and fall – the morning I wrote this my spouse slipped and fell while out walking Marlene.

HOW WIDE IS YOUR SIDEWALK?

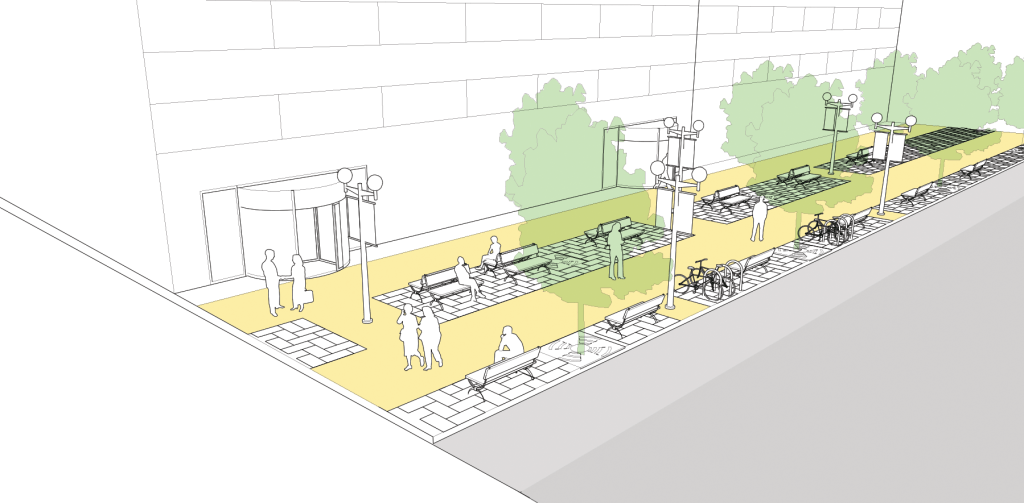

A city’s approach to sidewalks has a huge impact on the experiences of its pedestrians. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities and the National Research Council published Sidewalk Design, Construction and Maintenance, which “recommends a minimum Residential Street sidewalk width of 1.5 metres. When the sidewalk is located adjacent to the curb on major roadways, the width should be increased to 1.8 metres. The preferred width to provide for the safe passage between an adult and a person pushing a baby carriage or in a wheelchair, or a child on a tricycle is 1.8 metres.” Of course, there are often bits of infrastructure that take up space on sidewalks – signs, street lights, utility boxes, parking meters (!), bus stops, trees – so even the minimum width is often not sufficient for two people to walk alongside or pass one another, which is why the City of Toronto mandates that new sidewalks be at least 2.1 meters wide.

Cities also have to deal with design decisions of previous eras. The sidewalks in my neighbourhood in Regina, which was developed in the early 1900s, are about the width of the current minimum, but some North American neighbourhoods built in the 1960s and 1970s don’t have any sidewalks at all or only on one side of the street, and often those aren’t as wide as our current minimum. Sidewalk width is only one aspect of what a municipality can do to enhance its walkability. The U.S. based National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) offers some recommendations, “sidewalk design should go beyond the bare minimums in both width and amenities. Pedestrians and businesses thrive where sidewalks have been designed at an appropriate scale, with sufficient lighting, shade, and street level activity. These considerations are especially important for streets with higher traffic speeds and volumes, where pedestrians may otherwise feel unsafe and avoid walking“. We’ll look at other aspects of what makes a good sidewalk in future posts.

JEFF SPECK

In a talk for WRLDCTY, Jeff Speck, author of the book Walkable City that’s profiled on the Resources page, explains how people only choose to become pedestrians if the walk is simultaneously “useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting.”

DICKENS’S NIGHT WALKS

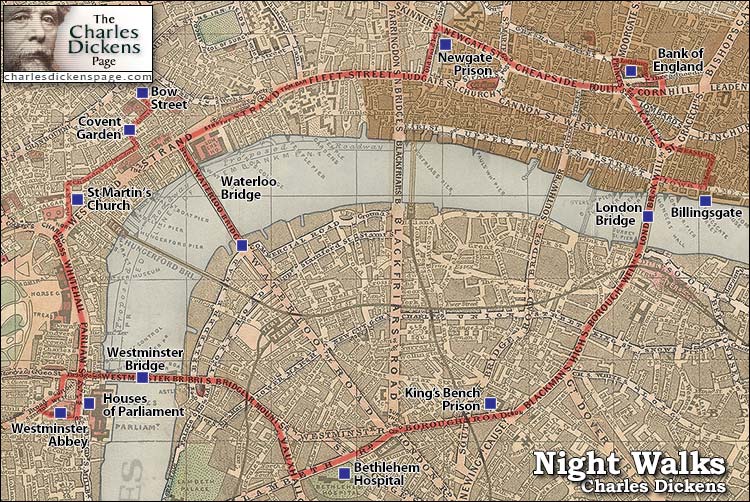

In my late teens and early twenties I read a lot of Charles Dickens. In Peter Ackroyd’s (unabridged) biography Dickens (1990), I learned more about the man behind the writing. An aspect of his life that really fascinated me was the long nocturnal walks Dickens would take to try and deal with insomnia and the racing mind that gave us Scrooge, Jenny Wren, Uriah Heep and hundreds of other characters. Dickens wrote about these night walks in a collection of essays first released in his weekly magazine All The Year Round, “To walk on to the Bank, lamenting the good old times and bemoaning the present evil period, would be an easy next step, so I would take it, and would make my houseless circuit of the Bank, and give a thought to the treasure within; likewise to the guard of soldiers passing the night there, and nodding over the fire. Next, I went to Billingsgate, in some hope of market-people, but it proving as yet too early, crossed London-bridge and got down by the water-side on the Surrey shore among the buildings of the great brewery.” These are now available in a volume titled Night Walks. I had intended to begin Project Pedestrian by retracing a Dickens’s night walk, but our dog Marlene had other ideas, so that trip to London was postponed. Perhaps some day.

LAUREN ELKIN

Lauren Elkin, whose book Flâneuse: Women Walk the City is profiled on the Resources page, contributed a radio essay to the BBC on the types of pedestrians one encounters on urban sidewalks: “Elkin reckons that the way people walk, their gait, is a signifier. It also tells us something about ourselves as we watch people file past us, the quick and the slow. And it makes her think of George Sand strolling Paris.”

WALKING IN SASKATCHEWAN

CBC Radio Saskatchewan’s Blue Sky devoted an episode to walking: “Ken Wilson spent days walking the car-centric bypass highway around Regina. He wrote about his experience in a new book Walking the Bypass: Notes on Place from the Side of the Road. Joely BigEagle-Kequahtooway of the Buffalo People Arts Institute did a ceremonial walk dragging buffalo skulls along what is currently known as Dewdney Avenue. She describes it as an act of reclamation. Hermes Chung wants to change the future of the Riversdale Neighbourhood by helping people remember the past and the Chinese history in that community. Alex Oehler discovered a love of walking grid roads. How has walking changed the way you see the world?”

THE ORIGIN OF 10,000 STEPS

We walk for a variety of reasons: transportation, exploration, contemplation. Over the past decade there has been a lot of attention paid to walking as a form of exercise, and the idea that one needed to complete 10,000 steps a day to get a worthwhile health benefit. The origin of 10,000 steps doesn’t come from science, but rather a 1965 marketing initiative by the Japanese company Yamasa to promote a pedometer they produced called the Manpo–Kei, the 10,000 step meter. The Japanese kanji character for 10,000 looks a bit like a human figure walking and that’s why they chose that number for the pedometer, and that’s how we arrived at 10,000 steps. This isn’t to say there’s not a health benefit in walking 10,000 steps a day (or 8000 or 5000) – of course walking is better for our health than sitting at a desk or lying on the sofa – but for me the health benefits of walking are a bonus, not the primary reason to do it.

WALKING ACROSS BRITAIN

The Canadian province of Saskatchewan – where Project Pedestrian originates – is 651,036 square kilometres, with a human population just north of 1.2 million. The island of Great Britain (England, Scotland, Wales) is 209,331 square kilometres with a human population just over 65.5 million. This perhaps explains why there are so many British TV shows devoted to walking; you can walk knowing you’re never far from a cafe, pub, inn, railway or bus station. An incomplete list of British TV shows based around walking – with anorak clad folks “setting off to…” – includes: Tate Britain’s Great Art Walks, Walks Around Britain, Coastal Britain, Wainwright Walks, Britain’s Lost Railways (the host walks around looking for them), Walking Britain’s Roman Roads, and a personal favourite Walking Through History, with Sir Tony Robinson (aka Baldrick from Blackadder), who also had a series where he walks Britain’s Ancient Tracks. What are your favourites?

CARDIFF WALKS

The Canadian artist Janet Cardiff works in a range of mediums, often in collaboration with her life partner George Bures Miller. Cardiff started creating audio walks in the 1990s. Designed for specific locales, the audio walks guide you along, in your headphones the sound of voices whispering, telling stories, giving directions, recorded sound fx blending with the sounds of the environment you are walking in. I’ve been lucky enough to do three of Cardiff’s walks: The Missing Voice: Case Study B begins in a library in Whitechapel and takes you on a journey towards Liverpool Street Station in London’s East End; Her Long Black Hair takes you through New York’s Central Park; A Large Slow River is set in the grounds of Gairloch Gardens on Lake Ontario, west of Toronto. The Cardiff walks are wonderful experiences. Every person’s walk is unique; the recorded soundscape stays the same, but the environment you’re walking in is always shifting and you bring things of your own to the walk. Here’s a short video illustrating part of what you might have seen and heard while doing The Missing Voice: Case Study B in London. You can find more about the work of Cardiff & Bures Miller at their website, or if you’re in British Columbia, at their Art Warehouse.

LYON

I started work on Project Pedestrian in March 2025 in a city I’d never been before: Lyon, France.

I didn’t know much about Lyon before going there and that was the point. Walking is a good way to get to know a place, and I wanted to learn about Lyon by walking in it. It was my good fortune to find myself in a city that had a plan to make itself pedestrian-friendly. Significant portions of Lyon between the Saône and Rhone rivers have been designed to give priority to pedestrians and cyclists. The result is substantial parts of Lyon have a lot of people walking and biking with limited vehicular traffic, and the loudest sounds are birds, people talking, and church bells. “The Lyon Confluence project is a unique opportunity to give the city back to its pedestrians.” You can read more about it via the link. Regina, Saskatchewan where I live, had a multi-year study to determine the fate of its block-long pedestrian street before deciding to retain it.

BLIND SPOT aka DIE REISE NACH LYON

One of the things that made me want to go to Lyon was the German film Die Reise nach Lyon (Blind Spot was its English title). Directed by Claudia von Alemann and released in 1981, the film stars Rebecca Pauly as Elisabeth, a young historian trying to trace the life of the 19th century writer and activist Flora Tristan. Walking through Lyon with a tape recorder, Elisabeth tells another character, “I want to imagine what she might have heard, seen, or felt. Colours, noises, all of that, in this town, Lyon, where she spent some time while travelling. I want to make the same trip.” The film made me curious about Lyon and its traboules, pedestrian passageways hidden behind doors that link buildings and streets. I enjoyed retracing some of the routes taken by the film’s character, and noting the ways the city had changed in the intervening decades and the ways it has remained the same.

GREEN KARL

The German city of Trier remembers its native son Karl Marx with a few transit signals near the street where he was born. Unlike where I live, pedestrians in Trier don’t need to press a “beg button” in order to get a green Karl, it’s a part of the regular cycle of lights. (Like Lyon, Trier has made the central part of the city a priority-pedestrian zone)

THE PROJECT PEDESTRIAN PLAYLIST

The playlist you didn’t know you needed? Perhaps. The Project Pedestrian Playlist gives you 100+ choice cuts about walking (OK, we know, sometimes they’re using walking/strolling/shuffling as a metaphor). The playlist is on Tidal, because Tidal pays the musicians more than Apple Music, and Spotify has a billionaire CEO investing in AI weaponry who pays the musicians even less than Apple. Best enjoyed while hoofing around yourself, the Project Pedestrian Playlist will walk with you to New Orleans, take you through London, Paris, and Memphis with Cher, on and in sunshine, and the rain. Enjoy!

WALKABLE CITIES

The American Geographical Society published a story on the world’s most walkable cities, and the winner is Milan, Italy! Three cities Project Pedestrian has spent extensive time in: Lyon, France (5), Paris, France (7), and Genoa, Italy (9), are in the top ten and we can understand why, we loved walking in them. 45 of the world’s 50 most walkable cities are in Europe, and the top North American city is Vancouver coming in at 53. “A walkable city is often defined as a city where you can walk to key amenities, like grocery stores, pharmacies, and schools. More specifically, the concept of a “15-minute city” asserts that cities can function more effectively, equitably, and sustainably if key amenities are within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. Walkable cities not only make daily errands easy, but they also encourage more physical activity and foster community.” If you want to see how your city is doing, you can look it up on the 15-minute-city platform; the city of Regina where Project Pedestrian is based averaged 17 minutes walking time for essential services, better than our rivals Saskatoon and Winnipeg. On a side note, WordPress’s spell check doesn’t think walkable is a word.

THE SONGLINES

An early influence on what is becoming Project Pedestrian is Bruce Chatwin’s 1987 book The Songlines, which made me think about walking as more than just a way to get from A to B. Chatwin’s biographer Nicholas Shakespeare writes about Chatwin and The Songlines. Michael Ignatieff interviewed Chatwin about The Songlines for Granta.

HERZOG & CHATWIN

In the winter of 1974, the German filmmaker Werner Herzog walked from Munich to Paris in the hope that this would prevent the death of his friend, the film historian Lotte Eisner, who was seriously ill. “I set off…believing that she would stay alive if I came on foot.” It took Herzog three weeks to make the journey, and while it may be a coincidence, Eisner recovered and lived nine more years. Herzog’s account of the walk was published as Of Walking In Ice. In 2019, Herzog made a film about another walker, his friend and the author of The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin. Herzog talks about Chatwin and the importance of walking in this interview.